Sir Richard Wallace and His Fountains

Originally, Sir Richard Wallace funded 40 free-standing, grand model fountains and ten wall mounted fountains, all placed at strategic locations. More of the grand model fountains were added when they proved to be very popular and practical, and as the Paris population expanded. According to British newspaper accounts and French historical records, Wallace funded an additional ten fountains in 1876 and ten more in 1879.1

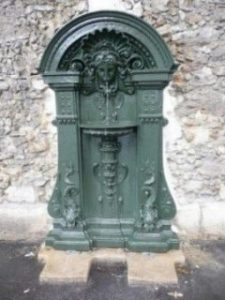

Two newer models were designed later, a colonnade model and a petit model, making a total of four styles called Wallace fountains, although only the original grand model and the wall applied model were Wallace conceptions. Today, there are 106 public grand model Wallace fountains in Paris, all of which dispense safe drinking water. In addition, one original wall model and two colonnade model fountains are still in existence and are included in the guided walks found on this website.

The grand model fountains were roughly designed by Richard Wallace himself. He drew sketches of the fountains he envisioned, incorporating in the drawings his desire for them to be useful, beautiful and symbolic. Then, Wallace hired his personal acquaintance, Charles-Auguste Lebourg, a highly regarded sculptor from Nantes. Lebourg was asked to improve the sketches and turn the practical drinking fountains into true works of art.

de la Ville de Paris, 1893.

Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris

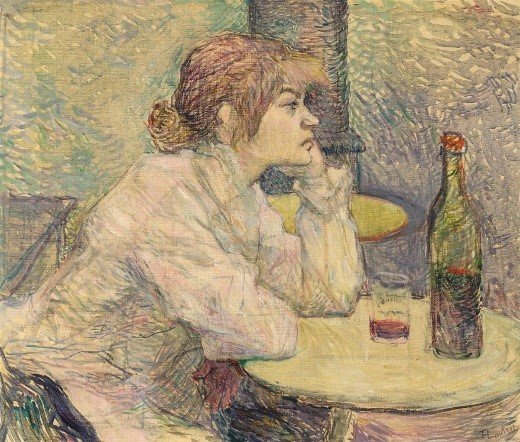

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon), 1887-1889

Oil on canvas; 47 x 55.3 cm. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum,

Bequest from the Collection of Maurice Wertheim, Class of 1906, 1951.63

Photo: Imaging Department (c) President and Fellows of Harvard College

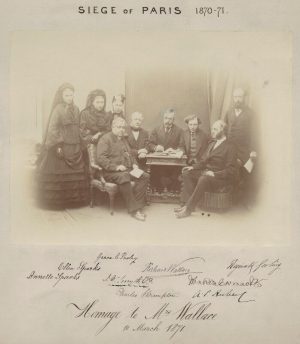

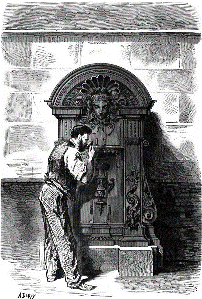

Wallace remained in Paris during the siege and the Commune period distributing his own funds for field hospitals, food aid, fuel and clothing for its poorest citizens. He saw firsthand the devastating effects of consuming alcohol when clean water was not accessible. In poor neighborhoods, Wallace must have witnessed “little ones, between two and three years of age, being fed on bread soaked in wine, and suffering from various ailments in consequence.”4

Sir Richard and others considered it a moral duty to keep the less privileged from falling into alcoholism simply because they had nothing else safe to drink. In the name of temperance, and from a sincere desire to use philanthropy for the common good, Wallace set about to commission the drinking fountains and deliver safe water to all.

of the British Charitable Fund after the Siege of

Paris. By Adolphe, albumen print, 10 March 1871. NPG x8892

© National Portrait Gallery, London.

Wallace Fountains of Paris are used by everyone, rich and poor alike, and it is not uncommon to see people of every station in life refilling water bottles at the fountains or cupping their hands to take a drink. Recently, Eau de Paris undertook a public service campaign to encourage use of all public drinking fountains and thus reduce the number of single-use plastic water bottles that harm the environment.

Wallace Fountains exemplify Sir Richard’s philosophy of giving a hand to those with an essential human need, in this case access to life-sustaining, safe drinking water.

His fountains also beautify Paris in a typical Parisian way – with style, artistry, symbolism, a nod to the past and a sense of monumentality.

From his earliest conception to the final design, Richard Wallace envisioned the fountains to be beautiful, as well as useful. Wallace and his father, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, were art lovers and art collectors. When the Marquess died, he left his art collection and a vast amount of wealth to his unacknowledged, illegitimate son, Richard Wallace. Their combined collection included furniture, sculpture, armor, medieval treasures and Renaissance works of art, as well as paintings from periods spanning several centuries. To prevent the collection from being destroyed during frequent civil unrest in the city, Wallace had it secretly shipped to England. Reflecting on his interest in the Renaissance art, Wallace also wanted the water fountains to be allegorical and to stand as symbolic reminders for users to adopt the best virtues of mankind.

Along with his conceptual sketches, Wallace also provided Charles-Auguste Lebourg with specifications and requirements for the design and construction of the fountains. His exacting guidelines referenced size, form, materials and cost. He specified the fountains must be “tall enough to be seen from a distance, but not so tall as to destroy the harmony of the surrounding landscape.” Their form must be “both practical to use and pleasing to the eye.” Their materials must be “resistant to the elements, easy to shape and simple to maintain.” Finally, cost was a major factor. Wallace wanted them to be “affordable enough to allow the installation of dozens.” 5

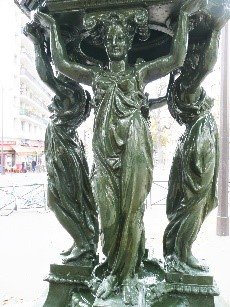

For the large, grand model, Lebourg created four caryatids, based on Wallace’s concept and possibly inspired by Jean Goujon’s caryatids located in the Salle des Caryatides at the Louvre. A caryatid is a classic Greco-Roman female figure used as a column or pillar to support an entablature or dome on her head or raised hands.

The four Wallace caryatids, holding up the dome of the fountain, represent four virtues – kindness, simplicity, charity and sobriety. Each figure is different and can be distinguished by the way each bends her knees and by how each tunic is draped. However, which caryatid is which virtue is not apparent to the viewer. Some believe the four figures also represent the four seasons and the passage of time and have identified them as follows: Kindness – left knee bent, knees covered, Winter; Simplicity – right knee bent, knee uncovered, Spring; Sobriety – right knee bent, knees covered, Autumn; Charity – left knee bent, knee uncovered, Summer.

The first Wallace fountains were produced by the Val d’Osne foundry. The grand fountain models were assembled from more than 80 pieces. The company owner, Jean Pierre Victor André, invented the ornamental cast iron process and he established a successful, award winning art foundry in 1835. The foundry workshop was set up in Val d’Osne in the Haute Marne region, but the company’s main office and showroom was located at 58 Boulevard Voltaire in Paris. Many of the fountains still operating have the Val d’Osne marking. Later, the fountains were produced by GHM Sommevoire, a competing company that bought the Val d’Osne foundry in 1931 and is still in operation.

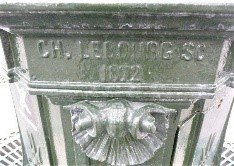

The earliest fountains carry two markings on the top of the eight-sided base pedestal. On one side is the name of the sculptor, CH. LEBOURG SC, with the year 1872, on the opposite side is the name of the foundry, VAL D’OSNE. This is a way to distinguish the early fountains or their parts from the later replicas produced by GHM. The GHM markings are found at the very bottom of the fountain base.

The city waterworks department decided the locations for the fountains donated by Wallace. The task fell primarily to Eugène Belgrand, Director of Water and Sewers of Paris. Belgrand was an extraordinary hydraulic engineer. He was appointed to his position as head of the waterworks by Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Baron Haussmann was the master planner Napoleon III put in charge of rebuilding the city.

While Wallace covered the expense to design and manufacture the first 50 fountains, as well as at least 20 additional fountains, this was a public-private partnership. The city of Paris provided the plumbing and installation. The total cost was estimated to be about 1,000 francs for each grand model and 450 francs for each wall mounted model.6

The first fountain, installed in July 1872, was placed on Boulevard de la Villette, but it is no longer there. The initial fountains proved to be so useful and popular the city of Paris, with generous support from Richard Wallace, soon authorized the installation of several additional grand model fountains. Sir Richard Wallace and his fountains were widely publicized and even the subject of a political cartoon. The Atlas Municipal des Eaux de la Ville de Paris, published in 1893 and available to view at the Library of the History of City of Paris, shows the locations of 63 grand model and eight wall model Wallace fountains.

Of the 106 grand model fountains currently present in Paris, all function and distribute potable water. Many have been moved from their original locations or added as the city underwent redevelopment over the last 150 years. It is not unreasonable to assume some will be moved or more might be added in the future.

The fountains operate from mid-March to late fall. Most are shut off during the winter to prevent the risk of freezing and damage to the internal plumbing. Eau de Paris is responsible for regular maintenance and repainting. One or two undergo complete restoration every year. A few fountains, mostly in the 13th arrondissement, go against tradition and are painted a different color than the standard dark green.

Sir Richard Wallace is best known in the United Kingdom for his extraordinary art collection donated to the British people. The Wallace Collection is available for public viewing at his former residence in London. In Paris, he is remembered for aiding the poor and for his generous, steadfast commitment to the common good as symbolized by the iconic drinking fountains that carry his name.

Richard Wallace died in Paris on July 20, 1890 at his home, Château Bagatelle, in the Bois de Boulogne. He was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in the Hertford-Wallace family tomb.

Footnote References

1. Shields Daily Gazette, March 20, 1879 and Dundee Courier, August 19, 1876.

2. The Fall of Paris: The Siege and The Commune 1870-71, Alistair Horne, Penguin Books, p.95.

3. An Englishman in Paris, Vol. II, The Empire, anonymously published and attributed to Sir Richard Wallace, later believed to be the work of journalist Albert Dresden Vandam, D. Appelton & Company, 3rd edition, p. 266.

4. Ibid. p. 306.

5. Wikipedia, Wallace Fountains.

6. L’Illustration, Journal Universel, vol. LX, no.1538, page 103.

©Barbara Lambesis 2019 All rights reserved

© La Société des Fontaines Wallace

All rights reserved.

Web Design by G6 Web Services

© La Société des Fontaines Wallace

All rights reserved.

Web Design by G6 Web Services